Step One is a podcast about people striving to change their world – our world.

We tell you stories from the Bosch Alumni Network, a network of doers and thinkers connected across the globe, working toward positive change.

Episode 6 – I Hear My Train A Comin’

© Step One, 2019

Introduction

This is STEP ONE

a podcast about people striving to change their world -- our world.

We tell you stories of the Bosch Alumni Network. A network of doers and thinkers connected across the globe working toward positive change.

From Berlin

I am Benjamin Lorch.

And today’s episode: I Hear My Train A Comin’

But before we dive into our story, we want to introduce you to the community this podcast is part of.

[Jingle]

It’s the Bosch Alumni Network, which consists of people who have been supported, in one way or another, by the Robert Bosch Foundation. The network is coordinated by the International Alumni Center, a think & do tank for alumni communities with social impact. The iac Berlin supports this podcast. If you want to know more about the power of networks, visit iac-berlin.org.

[Jingle]

Hey. You.

You listening?

I mean really listening?

What’s going on in your head right now? Are only listening to me… Or do you have some thoughts of your own?

OK, since you’re with me, I want you to check this out and try to really L I S T E N.

(pause)

I want you to meet Tiago. He’s going to tell us a story.

01 TIAGO VILLAGE

I grew up in a small village in Escapães right close to Santa Maria Da Feira where my father was born and my grandparents lived there.

...

My father used to tell me that he used the train to go to Oliveira de Mais to go to the commercial school where he studied when he was a kid.

(TRAIN SOUNDS

For me one of the most interesting stories that pictures quite well the time... He remembers that a cow was overrun by a train. Then the authorities came, the police came and they buried the cow for health issues. And the next day the cow the cow was already not there because along the line there was a several eh, a gypsy camp and obviously they took this opportunity. This is a whole cow! And they dig the cow. This is kind of stories that only happens in villages.

Tiago is an urban planner and historian. He likes to tell stories and to listen. Stories like the one of about the cow. These are kind of the local legends that bind people together in small towns, even if the stories – like all stories do – change over time.

The train has been an important part of Tiago’s life but today it’s not in the best of shape. It’s old and neglected, covered in graffiti and it’s rarely full of passengers. But Tiago, and a group of people close to him, want to revitalize the train and its stations and they think that stories, like the one about the cow, could play a central role in that effort.

(MUSIC)

Today we are going to find out how.

The train is here, let’s get on and begin our journey.

(TRAIN SOUNDS)

The rails we’re riding are called Vouga Line. They are named after the river which runs along. The tracks were laid in 1908, one hundred and ten years ago, before cars and modern highways came to the region. When it first opened, it ran over a 170-kilometer semicircle and linked the Portuguese countryside to the beaches where some people had summer houses. A seaside casino at Espinho was a big draw to a more urban, more cosmopolitan life, devoid of farms...and dead cows.

The line has just one set of tracks, so trains only ride in one direction at a time and the gage is smaller than most trains you might know but it is not exactly cute or touristy.

Today, parts of the line are closed so the system is a relic of what once was. It’s mostly used by students and older people without access to automobiles. Powered by diesel. Loud. Polluting. It’s not some sort of shiny, energetic train. Or not yet.

02 TIAGO DREAM

We have this very futuristic dream of having this railroad renovated and in better conditions to provide not only a good transportation system but also so that more visitors can see this territory -- to know its history, its culture because it fact it is quite interesting territory.

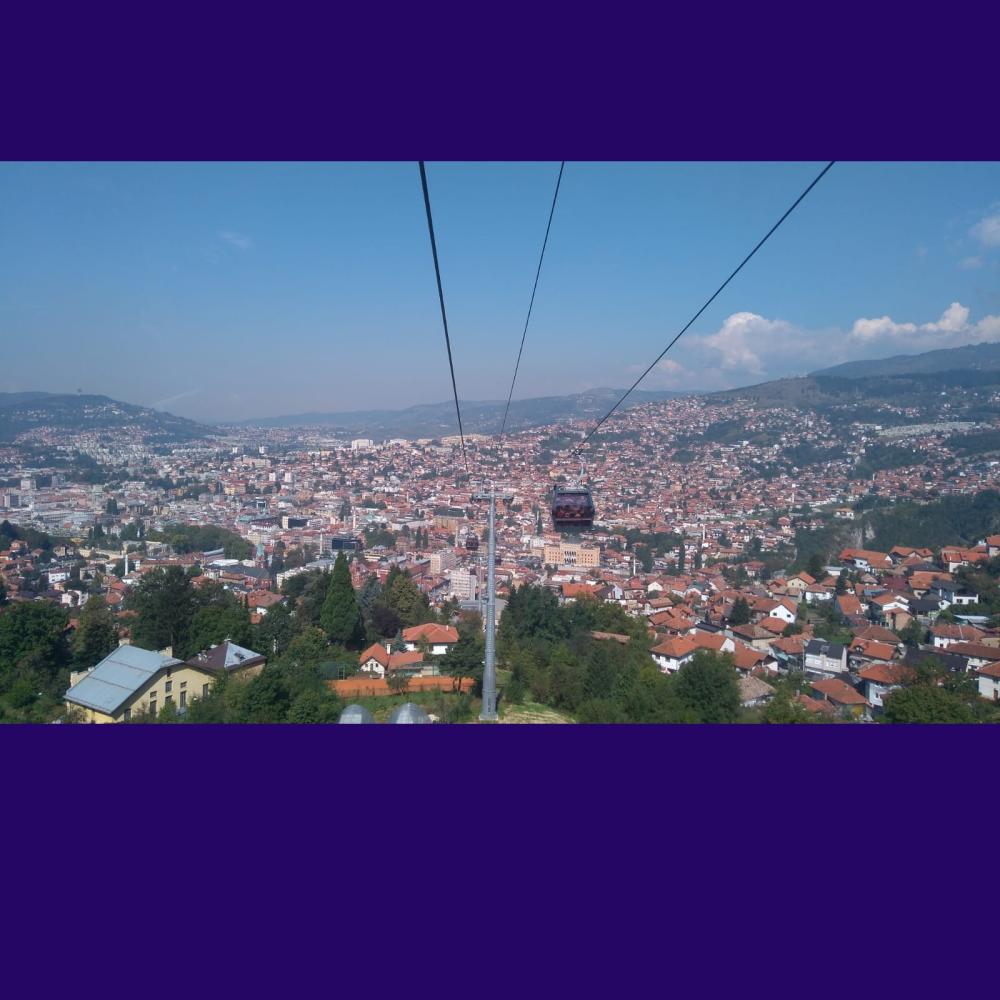

It is late November, and I am riding the train down to the sea together with Tiago, João and Karsten. Along the way we are going to pick Teja and Constança, two additional team members. All five of them, are urbanists and members of the Bosch Alumni Network, seeking to regenerate cities and regions through social engagement.

This is their second time meeting face-to-face in Portugal and they are riding the train together to lay down plans for their work. Their project is called Gardens of Listening - Back on Track and it aims at renovating that old train line and renewing a special bond: the old marriage between the train and the towns it passes through.

We roll through picturesque countryside, and towns such as

Oliveira de Azeméis, São João da Madeira and Feira. It is raining on and off as we pass farms and houses nestled into the hollows and valleys. Many of the houses are the first to be laid down here, long ago. Tiago explains to me that Roman roads first gave shape to the many settlements of the region.

Eventually we pull into São João da Madeira, a town of important industrial heritage, best known for its production of hats, footwear, pencils and a metalworking factory. As soon as we get off the train Karsten begins to take lots of photographs. Some graffiti sprayed on the wall of the station catches my attention.

03 GRAFFITI 00

Ben : Quiero Voga - - Read this to me.

Tiago : “Quiero Voginia ateo Porto”......The sentence means I want Voginia train up to Porto. So a proper connection between here and Porto.”..

It seems Tiago is not the only one with a dream to renew or expand the trainline. For people living in towns and villages in the countryside, having an improved rail train line would also invite tourists to the region.

São João da Madeira is small city of about 21000 inhabitants. It’s a pleasant, but a sleepy place. There is not much going on. We walk through a shopping mall built in the 80s, and it is depressingly defunct. The indoor market down the road is empty and quiet too. Tiago’s expression fluctuates between disappointment and hope.

04 TIAGO LET’S GO

Lets go over there . . .

After a short walk we enter an industrial area wedged into the cityscape. This is where a big metalworking factory called Oliva was located. It employed many in the region. This iron and steel works produced sewing machines, farming tools, even at one point small combustion engines.

05 TIAGO OLIVA

We are looking at the industrial complex of of Oliva that was one of the biggest metal factories in the country. They started to make taps and other parts for plumbing; metal tubes … but along the years and decades they started to do all kinds of materials like fridges, and sewing machines, even televisions, radios, all kinds of stuff. And in the 80s, like most of the industry, it started to collapse.

These goods were exported around the world, particularly to Portuguese colonies. But global competition encroached. The factories closed and jobs disappeared. The region went into economic decline.

Now it is quiet in the factory complex. The buildings are closed up. Some of the roofs have fallen in. The area is deindustrialized. Ghosted.

Through the rain Tiago leads us to one part of the complex that is lit up bright and refurbished. It’s the Oliva Creative Factory which houses a startup center, a few shops and a museum. Creative Factory has all the outward signs of hipster coolness: plywood furniture, a fixie bicycle leaning up against a black chalkboard wall, exposed brick and fancy vintage-style light bulbs but there is no one there when we visit...

TIAGO ARTISTS

If you had a really good train to bring visitors here and also to bring artists and to take artists to other places then you could actually create another kind of movement. Artists like to be on the edge of creation and normally it is in cities where they feel inspired, very few like to stay in small places... they feel trapped so

For Tiago and the group, the train could be a lifeline to connect the small villages to larger towns and cities. If it were modernized, it could draw for not only artists but also tourists to the region.

It is dark out as we leave the Creative Factory and walk down the hill to return to the train station.

07 TIAGO CLOCK

Tiago: And you can actually see the state of the building it’s abandoned, its closed, its derelict even the clock is completely destroyed…you can see only the numbers . . .”

This clock at the train station is a slightly terrifying sight - a clock face without hands. Unprotected by any glass, the white paint is weathered away. The numbers are still clear -- bold and black standing there, facing the tracks. They are strong and can be seen from a distance . . . but there is no time.

It is not that time has stopped --it’s just uncounted here.

Actually, it feels kind of symbolic. Not just this clock, but all of the clocks along the line are this way. Because the train brought precise industrial “railway time” to the region over 10 decades ago and now these clocks no longer measure the time or set the pace for the people here.

At the train station in São João da Madeira, there are only few people, waiting for the train. No one is talking to each other. They look to me like a collection of glowing blue ghosts with their faces each illuminated by their phones. Everyone is looking at their phone. Nobody is talking to each other. They are standing there, alone together.

Tiago and his team want to change this. The way they see it, improved train service could provide more than just transportation for people in the region. It could change the way people relate to one another, the way they talk and listen to each other -- the way they engage with the community that surrounds them.

But, how?

(music transition)

It’s Thursday now. The Back on Track Team boards the train and heads to the coastal city of Espinho. And this day also happens to be the 110th birthday of the train. As we ride the train, something unexpected happens.

08 TEJA MUSIC STORY 1

So we board and look, There is this guy! With a accordion. Ah, What a lovely accordion. I am completely amazed by looking at this instrument.

This is Teja, a member of the team and expert on the renovation of cultural heritage sites. At that moment, she is sitting next to Karsten who tells her he was in Romania just last week, and he got invited to a birthday party, he learned a song. So he start to sing. And the guy with the hat..

And the guy, from this musical group turns…

Oh! Romanian! this is Romanian! And they start talking. And so Karsten immediately starts interacting with him. And the guy starts playing. We sing, we dance. Karsten gets up! and he starts waving and dancing and everything. The guy from the musical group is constantly saying thank you madam, God Bless You.

Karsten goes to the front to maybe introduce, to explain to the people because they are startled. They pretend they don’t see us. That we are not there. What is going on? Yes.

(MUSIC TAPE OF SLIGHTLY WILD ACCORDION MUSIC)

Somehow no one the train really seems to care what is going on. They stay focused on their mobile phones while we carry on with the musicians sharing a little bottle of local brandy that appeared out of nowhere. There are some smiles among the people but we, the outsiders; and the musicians are really the only people engaged and enjoying the scene.

When Karsten stops the accordion player to publicly explain that this day -- this very day -- is the birthday of the trainline....some people smirk but no one really seems to care.

Karsten

Do you know about this?

Today is the birthday of this train.

Constança Translates

Disconnection and disengagement is of course not specific to this region. Listening to people, and especially listening to people at length to really understand what they are saying is just not something we – well, on a global scale -- are very good at doing these days.

Would you agree?

To find out more, I Googled some stuff.

(** Sound of typing **)

“Short-en-ing at-ten-tion spans”

Hmmm...OK, here we go.

So according to a research published by Microsoft in 2015, our attention spans have dropped in just the span of the past 15 years. In 2000, people were able to stay on task for an average of 12 seconds.

But, in 2015 it was measured to be, on average, just 8.25 seconds. Eight and a half seconds is less than that of the everyday goldfish, which clocks in at an attention span of a whopping full 9 seconds.

These findings have been disputed but

the thing is -- a good story takes more than 8 or 9 seconds to tell and a productive conversation certainly takes much longer than that. Like that cow story that we listened to at the beginning? It lasted at least a minute. And so often we don’t seem interested in taking that much time to fully listen to each other.

As Karsten puts it, it is listening without connecting.

09 KARSTEN LISTENING

Mostly the people around us are listening to get answers and not to understand. Its is just answering. It is not listening, it is not understanding, it’s just exchanging snippets

And I really, really suffer with this because I think to understand things, to understand one another's opinions or needs or wishes, you have – first you have to kisten to listen

Karsten, in contrast, has developed his own way of getting into conversations, with people when he visits places -- just as he did on the train.

10 KARSTEN ENCOUNTERS

So, when I go to a place I have never been before.

I never research anything about it. So I am just, this is a white sheet of paper. And then I am in the position to need help for everything. I have to ask everyone for help. And that brings me a bit under the eyeline of the locals and so they can help me and then we can have an encounter. And I have to create some encounters because I have to ask for everything.

He looks and he explores directly -- looking and being looked at, listening, talking, looking and listening again.

But is this the approach of creating encounters the right one for everyone -- even for the team of the Back On Track Project?

Riding the train again, Tiago and Karsten explore this important question about how to engage the people of the region and talk with them.

11 K & T CONVERSATION

We need to put ourselves at their level. Or… its always doubts that I have. In terms of speech. In terms of communication or

. . .

Karsten:

This is something I dislike so to say that we need to bring ourselves on their level so . . .

Tiago: No, no, when I say, in terms of communication. I already saw in some situations. In this participatory process. Who is running it, they keep themselves on a higher position. Like I am the one who has the whole knowledge. I am the one who came here to solve your problems. And I hate to be, I hate to give that impression. I want to become a better urban planner and better facilitator, urban mediator and so we need constantly evolve the way we read people, the way we analyze people. NO?

Karsten: No, no, no. Don’t do that. Don’t analyze or read.

Tiago: In the way of trying to understand…

Karsten: Yes but there are different ways. If you try to analyze you are always on a higher position. You come there and this is your field of studies and you study somehow the people. And I think this is the wrong way.

Tiago

I normally tend to be myself and I like to engage. I like to sit down with an old lady. Have a really nice tea and knowing her life.

Karsten: If she is not interested. And she has the right to be not interested in something and we have to respect this. I think the most important thing is time and trust. And for trust you need time.

There is no conclusion, no resolution. After this conversation, they both fall into a respectful silence -- thinking.

(BELLS VIBES AND OCEAN SOUND MONTAGE)

Now at a beach hotel in the coastal city of Espinho. Karsten, Tiago, João, Constança and Teja sit in deep cushy chairs in the lounge area of the hotel bar where we are staying. The space does not seem to have changed at all since the hotel was built in 1973.

The group is here to solidify their plans for the coming year and formally kick-off the Back on Track project. Post-it notes cover a low marble table in the center of the group.

Constança, an expert in design thinking and the group facilitator, summarizes the plans.

12 CONSTANÇA FOCUS

So, the focus for the first year will really be about listening and reading the territory and the needs of the community. With the emphasis on the train and the role of the train and also creating the engagement network for the project, for the outputs for the network or any other things that might emerge from this project.

And then, Teja steps in.

13 TEJA OPPORTUNITY STORIES

In this European setting it is important to give the people the opportunity to share their stories about their daily lives, about their experience of the buildings and environment and artifacts and everything, you know.

In this first phase of the project they will commission photographers and sound designers to photograph and record the trainline and its people. Their hope is to elevate awareness of the train as a real asset to the region. Exhibitions in the towns and in the stations along the line will reflect and echo the line and its communities back to the people while the team and looks and listens for responses.

If they succeed, they could transform the region through improving transportation. But they could also improve the quality of the conversations and connections between the citizens.

Travelling together along the train line has brought the project group together and they feel it could work for other people as well. If their method works, they’d like to take it elsewhere and change the way the rest of our noisy world works too.

This is their Step One.

(CAR NOISES)

On my last day in Portugal, João drove me to another train that would take me to the airport. Shortly I would be returning to Berlin while he and the others would continue to work on the project for a few more days.

I think this is a very political project. If we promote this active listening, if we promote this active vision and definitely to think about what others have to say. This is a very political -- a very very strong political statement.

Right now it is all about traiding. We are all pushed to trade something. So, I am going to speak with you because I want something from you. I want to trade something with you. And that’s it. The base of politics today is all about this.

And I think there is such a potential for being something else, right?

Words are powerful

and can be used in so many ways.

Words make worlds

and only we humans were given this gift of language.

When we exchange words with one another, we can do so with care or indifference, even violence.

But when we listen and speak with patience and understanding of each other, we engage in the most graceful act of giving and receiving. A beautiful recognition of the other.

In this way -- it has been said -- that Listening is an act of love.

João: People really need to give more affection to each other.

People now say, ‘oh affection, that is so silly’ and people waste it completely. And Really I do not know why because that is the thing that makes us humans. It’s really what makes us connect with each other and what makes us want to be with each other. Right? And there are so many amazing ways for us to be together and to connect with each other, you know.

In the car now, With all that I asked João how he was doing and how he thought the Gardens of Listening project was progressing.

“I am in Heaven,” he said.

And as I listened to João say that, I was there with him too.

Thanks for listening.

This has been Episode Six of Step One.

Reporting by me, Benjamin Lorch.

Our editor is Jelena Prtoric, our producer Yannic Hannebohn.

Our theme music is composed by Niklas Kramer.

A special shout out this time goes to the whole iac Berlin crew that supported us throughout this first season, especially Lucie and Alexandra and Lisa - this would not have been possible without you.

The teams whose voices you hear in the piece and our team, too, we’re all part of the Bosch Alumni Network.

This was the last episode of the first season of Step One.

Will there be a second season? Maybe.

We’re evaluating our options and hope to be back later this year with fresh stories. If you have ideas or suggestions, we would love to hear from you.

Remember the next step is always step one.

This is Benjamin Lorch and thanks for listening.

Transcript

Episode 05

"Leave the gun, take the cannoli"

© 2018 – Step One Productions

Intro.

This is STEP ONE

a podcast about people striving to change their world -- our world.

We tell you stories of the Bosch Alumni Network. A network of doers and thinkers connected across the globe working toward positive change.

From Berlin

I am Benjamin Lorch.

And today’s episode: Leave the gun, take the cannoli

But before we dive into our story, we want to introduce you to the community this podcast is part of.

[Jingle]

It’s the Bosch Alumni Network, which consists of people who have been supported, in one way or another, by the Robert Bosch Foundation. The network is coordinated by the International Alumni Center, a think & do tank for alumni communities with social impact. The iac Berlin supports this podcast. If you want to know more about the power of networks, visit iac-berlin.org.

[Jingle]

Jelena: It is a nice and warm Saturday in May 1992, and Antonio Vassallo sits on the terrace of his family house, in a small Sicilian town right outside of Palermo. Antonio is 26, he is a photographer and he is just putting a new role of film in his camera, preparing for an afternoon gig, when he hears a deafening explosion.

Antonio: Quel pomeriggio mi trovavo qua giù a casa, nel terrazzo esattamente. Stavo preparando la macchina fotografica, stavo montando un rullino perché la sera avrei avuto un servizio fotografico e sento questa esplosione potentissima.

Antonio is somewhat accustomed to the sound of explosions. There are two stone quarries in town, and pretty much every day one can hear detonations. But this explosion is different, much more powerful. The windows of his house are shaking.

Antonio: Personalmente mi è bastato girare lo sguardo in direzione di autostrada vedere questo grande nuvolone di fumo..

Jelena: Above the highway, some 200 meters from his house, he sees a cloud of smoke. So he puts his camera around his neck, gets on his scooter and heads there.

Antonio: Sono costretto a lasciare il motorino appoggiato ad un albero circa 100 metri prima perché era impossibile proseguire perché l'autostrada che non c'era più era ricaduta tutta....

Jelena: It is impossible to get to the highway on a scooter, there is rubble everywhere. Olive trees are down, lying around, the air smells of explosives...And a large part of the highway is simply - missing. There is a huge hole where the road used to be. There are some other people around, some farmers working on their land nearby. They start to gather, and Antonio after some time scrambles to the remaining part of the highway. On the road he sees a white car, demolished.

Antonio: Noi diamo un’occhiata all'interno di questa macchina e vediamo quest'uomo alla guida...

Jelena: Antonio and the others approach the car. Inside they see two men and a woman. The face of the driver is covered in blood.

Antonio: ...gravemente ferito, al torace, alle gambe, sanguinante in viso. E ancora con gli occhi aperti.

But he is still breathing; his eyes are open, and Antonio catches his gaze.

Antonio: Io quello sguardo l’ho incrociato per un attimo.

The man will die in the hospital that evening. His name: Giovanni Falcone. A famous prosecutor, one of the symbols of the Italian state’s fight against the mafia. And Antonio is among the last people to see him alive.

(music)

Jelena: The killing of Giovanni Falcone is known today as “Strage di Capaci”, or Capaci bombing because it took place on the highway crossing the town of Capaci. Mafia members put more than 400 kilos of explosives in a drainage tunnel under the highway. The bomb killed Falcone, his wife, as well as three police escort agents. They wanted not only to get rid of Falcone, but also to send a message - you don’t mess with the mafia.

Ben: Wow, that’s unbelievable.

When Antonio looks back at it today, he says that this death has changed the course of his life, and in general, Sicilian society.

Ben: What do you mean?

Jelena: Well, Falcone’s killing was the sad climax of a series of crimes that the mafia committed in Sicily in the ‘80s. It might seem unreal but there was a time in the Italian history when the very existence of the mafia was considered almost an urban legend. But then, the violent 80s came.

Edoardo: So, I was born in 1975, but during the ‘80s when I was ten for example, you know, I could see with my eyes all the violence of the mafia and let's say that the worst moment, the worst period of time for Palermo was for sure, let’s say between the late ‘70s and the early ‘90s. What we call usually the long ‘80s.

Jelena: This is Edoardo Zaffuto, Palermo born and bred. He showed me around Palermo. The city is stunning. For me, it is hard to imagine that Palermo was ever anything but an easy-going city. For Edoardo: not so much. As we drive outside of the city, towards the beach of Palermo he tells me that while growing up, he often wondered why of all the places in the world he had to be born in Palermo?!

Edoardo: Imagine that, at the beginning of the ‘80s, in particular, there was one of the most violent mafia wars in the history of Cosa Nostra, of theorganised crime. During that years, the mafia were killing each other and there was one year in which there were something like 1000 mafia murders in Palermo. So imagine 3 murders per day, on average.

Jelena: The mafia committed crimes so violent that eventually a special anti-mafia pool was formed and, in 1986, a trial started. Giovanni Falcone was one of the main anti-mafia prosecutors. The trial was known as “Maxi processo”, a “Maxi Trial”?

Ben: A Maxi Trial?

Jelena: The ‘maxi’ stands for the importance of it. The trial lasted until 1992; almost 500 people mafiosi got convicted and the existence of Cosa nostra was finally confirmed in court.

(historical tape)

The trial is still regarded as one of the greatest successes of the Italian judiciary system and the biggest anti-mafia trial in the country’s history. It was a sign the mafia is not outside of the law, untouchable. It gave hope.

Ben: Right.

Jelena: But then, the mafia killed Falcone.. Less than two months later, in July 1992; another prominent anti-mafia judge and Falcone’s friend was assassinated as well. Paolo Borsellino. A bomb was planted in a car parked in front of his mother’s house in Palermo. Two murders in less than two months. It shook up the Sicilian society. Everyone who I talked to, told me they know exactly where they were and what they did when the murders happened.

Ben: Hah, just like 9/11?

Jelena: Exactly. It provoked a lot of emotions, especially among younger people.

Edoardo: That was like, that was too much, I mean, not again, all the people started to say not again. It was rebellion of the people who said - enough. You know, I was probably still young, but that was a moment in which some seeds have been put in the ground, not for only me, but my generation as I say.

(music)

Jelena: These seeds, as Edoardo puts it, grew to become an important project in Sicily. And also, it is exactly because of the Capaci bombings that the paths of Edoardo and Antonio will cross years later.

Jelena: But before we get to that moment, let me tell you the story of how I met Edoardo.

Ben: Where was that?

Jelena: I was in Palermo for an event named “Trust and Transparency”, organised by members of the Bosch Alumni network. The idea of the conference was to enhance trust and communication between public administration, media and businesses. And Edoardo was one of the speakers there.

(music end)

To understand why mafia was able to become so powerful in the first place, it is crucial to look at the concept of trust.

Ben: How can you conceptualize trust at all, what’s the basis?

Jelena: Well, you can start by understanding the concepts that you already know, that are familiar to you. This is why we began by looking at trust between individuals, then between institutions.

Vitor: First of all, trust is about taking chances, assuming a risk.

Jelena: This is Vitor Simões, a founder and coordinator at 4change, an organisation specialized in communication and consultancy, based in Portugal. Vitor wrote his thesis on trust.

Vitor: You can only trust if in the meantime you assume your vulnerability; you cannot trust if you are closed in yourself. You have to assume risk. It assumes a voluntary cooperation, so trust can be instilled through control and fear but in the long run, it is not a productive way to instill trust. Trust is better if you do it voluntarily and in a cooperative way. You cannot build trust based on laws.

Jelena: In a personal relationship - be it in friendship or in love, we usually need a lot of time to start trusting the other person. You need to trust that somebody will not betray your confidence, you need to believe that another person will not hurt your feelings if you show them how you feel. And this simple concept also applies to professional relationships.

Let me ask you something

Ben: Sure, go ahead.

Jelena: At work, have you ever been in a situation where you had to do something that goes against your values?

Ben: That’s a good question, let me think. All right, in one of the schools I worked for, one of my tasks was to get people to apply to scholarships. It was the first one we have ever had. And once we had this very qualified applicant so it seemed logical to me that she would be given the scholarship. And that what was on the lips of everyone.

But then, at the very last moment - and I was in touch with her about all of this - I was told somebody else would get the scholarship. And this person didn’t really need the scholarship, but he was a very famous face on television, and the school management wanted his very famous face in school.

Jelena: So, what did you do?

Ben: WelI, I had to get back and talk to the first woman and tell her that she would not get the scholarshi, even though it seemed inevitable. It was actually awful. I was horribly disappointed by the school management and the position I was put in. The trust I’d established with the first applicant was totally shattered. I felt sick about that. And the trust I held with the school was also damaged.

Jelena: So it’s funny because some of the participants in Sicily had very similar experiences. They lost faith in their coworkers or bosses – in public administration, media or businesses, wherever they were working. Here is one of the examples:

Conference case (woman speaking): ... So one ministry of Education got the grant and it was supposed to provide equipment to schools. And suddenly my manager, who is my direct supervisor, decided to add one additional school, besides those five, that were first selected to get the equipment..And then I have found that he did that because he had a friend who will actually buy the equipment for that school...

Jelena: This was one of the cases we discussed in small groups. I can’t play you more of these, since they were very sensitive cases and could potentially endanger the participants if they were made public . But we did come up with a list of dos and donts for each case. And we also discussed how trust in institutions could be enhanced.

Vitor: If you don't trust the formal aspects of your life, like governments, you kind of search refuge in the not formal aspects, like your family or your neighbourhood. And here in Italy, and in Sicily, you have a good example of that...If the government is not responsive to you, if its rules are not enforced, you go for the rules of other entities not so explicits and not so formal, like mafia, and others...

(music)

(sounds of Sicilian streets)

Jelena: Buonasera

Raffaella: Buonasera

Jelena: It is not by accident that we were discussing Trust and Transparency in Sicily. It’s here, where the trust in government was low enough to enable the mafia to spread its influence.

Raffaella: La mafia è nata nel momento in cui c(è stata l'assenza dello Stato...

Jelena: I visited Raffaella Candido in a small hat shop in Palermo she runs.

Raffaella: Era l'antistato. Quindi la mafia faceva quello che lo stato non faceva. Proteggeva. Aiutava i più poveri…

Jelena: In her words, the mafia was actually born from “the absence of the state”. They offered protection to those the state didn’t protect. They positioned themselves as Robin Hoods in a way, protecting the poor. They even call themselves “uomini d’onore”, men of honor.

Raffaella: Ma infatti si diceva “uomo d’onore”, lo si chiamava, “uomo d'onore” perché una sua parola data era quella.

Jelena: Raffaella says “men of honor” comes from their integrity.

Raffaella: Non avrebbe mai cambiato l'idea. Si io ti dico; sta tranquilla, me ne occupo io;

Jelena: If they would give you their word, they would live up to their promise, stand their ground.

Raffaella: Se ne occupava lui.

Jelena: They would protect you…

Raffaella: ….e non poteva mai cambiare l'idea....

Jelena:... if they said so.

Ben: So they were filling in for a state apparatus that couldn’t provide the kind of trust that was needed.

Jelena: I would say that rather, they tried to portray themselves as a substitute for the state apparatus.

Ben: That is pretty smart. But were there actually a lot of threats they protected the Sicilians from?

Jelena: Of course no, it was more of a marketing campaign, you could say.

Although the mafia men presented themselves as protectors and good doers, they were always expecting something in return. They didn’t do favors. And of course, if you’d disobey them, if you would not show respect, you’d be in a problem. Raffaela herself actually had a close encounter with mafia, couple of years ago.

Ben: Oh really, what happened to her?

Jelena: So, as I mentioned, Raffaela runs a traditional Sicilian hat shop in Palermo. And I think you would like it a lot actually, there are hats of all colors and fabrics on shelves around the room.

Ben: Ok you have my attention, I like hats. What is a traditional Sicilian hat like?

Jelena: Now you can buy them in all the colors and they can be made of nice fabrics, but Raffaella explained me that a traditional hat is flat and was made of cheap, black fabric.

Raffaella: Allora, la coppola nasce di panno nero e spiego perché, perché anticamente...ed era usata dai contadini. Perché di panno; era il tessuto il più povero che esisteva. Ma pensarono a questa forma di cappello perché doveva servire per lavorare i campi, quindi non doveva dare fastidio, e….

Jelena: These hats were initially worn by Sicilian farmers. The hat has a short bill, important for farmers because it protected them from the sun while working in fields. And Raffaella says these hats were an important part of the Sicilian identity. She remembers her grandfather donning these hats, called coppolas in Italian, even when he was at home.

Ben: Wait, what Coppola? Like the film director?

Jelena: The pronunciation is the same, yes. And actually, you see coppolas in Coppola’s Godfather. Have you seen the movie?

Ben: Yes, of course I have seen the movie, but it was years ago. Ok, refresh my memory; where are the hats in the movie?

Jelena: So you know when in the first Godfather, Michael Corleone goes into hiding in Sicily because he killed two men who attempted to assassinate his father. So, he is in Sicily and is walking in the middle of the fields with two other guys…

(Godfather tape in the background)

And then stumbles upon Apollonia, and he falls in love with her at first sight and she becomes his first wife.

Anyways, the story is that while walking through the fields, Michael and his men are wearing coppolas. And the thing is that the mafia appropriated it as a piece of their identity. To the point that ordinary citizens actually stopped wearing the hats.

Raffaella: Con l'andar degli anni, questo copricapo non è stato più portato, perché? (In the background: Perché comincio ad identificare solo ed esclusivamente gli uomini di mafia, gli uomini d'onore, perché solo loro la portavano.)

Jelena: While the farmers would wear their coppola straight, the mafia would wear it slightly bent on one side. For many years you could see men with hats bent to one side walking the streets of Sicily: Until one man had the idea to “give back the dignity to the Sicilian coppola, to make it a hat that ordinary Sicilians would want to wear again. He reached out to Raffaella’s father to help him out - her father was in the clothing business. Raffaella eventually ended up running the store that sells these hats.

Ben: Amazing.

Jelena: And the business does well, she told me. Coppolas in various colors have become a fashion accessory, many tourist buy them as a souvenir from Sicily. In December 2013, Raffella had another store opened in town, at another location. It was a temporary shop, just over the Christmas holidays. But several days after setting up the shop; they could not open the door.

The lock was filled with glue.

Ben: Coming up after the break: Palermo resists.

(plug to Project ungoverned)

Hi, I’m award winning author Nicole Harkin.

And I’m Dr. Kim Ochs.

Are you interested in other podcasts that take place within the Bosch Alumni Network?

In our podcast, Project Ungoverned? The Online Learning Landscape, we speak with educators, learners, and pioneers in online education from across the globe.

We examine new possibilities, challenges, and innovative organizations in online learning. K: The Project Ungoverned? podcast is out now. Listen to it wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also find us at projectungoverned.com.

(end of plug to Project ungoverned)

Jelena: Raffaella knew what glue meant. A warning from the mafia. It is their way of saying that if you don’t pay money to the mafia you are “not getting into your shop”. Even worse: Ignore the warning and - your shop will get demolished, eventually, could be set on fire. Raffaela had no chance but to do something.

Ben: So what did she do?

Jelena: I will tell you about that in a second.

Ben: And so this extortion money is paid by everyone in Italy?

Jelena: There have been some estimates in the past, so yeah, a lot of people allegedly paid protection money, but it is very hard to determine what’s the percentage of the businesses do it.

Ben: Ok, I can understand that.

Jelena: Ok, and what is important to know is that the pizzo, an this is the way they call protection money in Italian. It is one of the ways in which that mafia actually establishes their “rule” over a territory. The money itself is not that important - if you have a small business you might pay something like ten or twenty euros per month; so almost nothing. If you have a bigger business, you would pay more, of course. What is important is first and foremost that you “acknowledge” their presence, that pay respect. Nowadays, pizzo is still present in Sicily, in Palermo, but much less so since 2004.

Ben: Oh really, 2004, what happened back then?

Jelena: So one morning in 2004, the city of Palermo woke up covered in stickers.

Ben: Stickers?

Jelena: Simple stickers, simple action. And the stickers read “un intero popolo che paga il pizzo è un popolo senza dignità”. Which you can translate into “an entire population that pays protection money, is like a population that has no dignity left”.

Ben: But who put the stickers around?

Jelena: People had no clue. But, we already heard from Edoardo who showed me around Palermo. In 2004 he is working in a small publishing company. The business is not flourishing, they don’t make a lot of money. And one of Edoardo’s colleagues, Vittorio, plans to open a pub in Palermo with several other friends. One of them writes a business plan so he lists all the expenses for their future business. You know. He puts rent, he puts supplies on this list; he puts like administration, whatever, and then he puts - pizzo, protection money.

Ben: As a line item? Ok!

Edoardo: It was a provocation of course, but it was an excellent provocation because all the other people of that group started to say of course we don't want to pay the money. Are you crazy, you put it in business plan and we did not even start yet, we don't even know if we will start it...But actually it’s there, and he said you know what – this is normal here in Palermo.

Jelena: The fact that people perceive pizzo as something normal upsets Vittorio, Edoardo’s colleague. So he comes up with this catchy phrase and one night he posts his stickers all around the city. And this is a very strong message. I mean, Edoardo explained it to me. It touches on the concept of the Sicilian dignity - and Sicilians are super proud. This action was repeated over the next couple of months.

Ben: Ok, but weren’t they also scared that mafia could get them?

Jelena: Yes they were actually very scared. When they started the website, every time Edoardo would want to work on the website, he would go to a different internet cafe; just to be able to change locations so that he does not get caught by the mafia. And every time they would run their sticker actions; they would do it during the night. So every next first step had to be carefully planned. However, at some point they realized they needed to shift tactic.

Ben: In which direction did they go?

Jelena: So, at the beginning this was more of a protest action for them. But then the idea of the critical consumption appeared. They thought it was wrong to call out shops that paid protection money’, so they did the opposite. They wanted to set up a list of shops that didn’t pay. They knew it would be hard to get businesses on board though, because they weren’t the first to attempt such a thing.

Ben: How so?

Jelena: It was in 1991 when a shop owner was gunned down by the mafia because he had been reporting mafia threats to the police and published it in a local newspaper. And no one would back this poor guy,

Edoardo: So what we did, before going to the shop owners, we said let's go and put together a group of townspeople, of citizens who said that in the future; when there will be a list of mafia free list, a list of business that don't pay the protection money, I will support this network, I commit myself to do it.

Jelena: They turned to customers first, asking them if they would support the businesses that don’t pay the protection money. More than 3500 people signed this petition. The names were published in a local newspaper. And it rassured the shop owners, they felt that there was a critical mass of consumers that would support them, that there is solidarity

Edoardo: So, with this list it was easier to go to the shops and say, knocking at their door basically, as you can see you will not be alone, there are already 3500 people ready to support you.

Ben: Alright, and did it work?

Jelena: They started with some dozen shops, and now they are over 1300. So it is not really an exponential growth, but they achieved that pizzo isn’t seen anymore as something normal in the society. Here’s another thing. Every Addiopizzo member gets a small sticker with inscription of Addiopizzo and a sentence saying “pago chi non paga”, or “I pay to those who don’t pay”.

Edoardo: This is a new promise we can give, it is like, if you put the Addiopizzo logo on your window, so if you join Addiopizzo in your window and put that sticker in the window, be sure that the mafia is way less inclined to come to your shop. This sticker means “be aware because I am with Addiopizzo - if you come here for the first time asking me for money, I will go to the police, I will go straight to the police”. So these stickers keepz the mafia away from the shop.

(music)

Ben: But did Raffaela have one of these stickers?

Jelena: So her shop is also a member of Addiopizzo network. But the other shop, the temporary shop, the one that got glued, didn’t. However, Raffaella contacted Addiopizzo, they went to the police together, denounced the threats. She received no threats afterwards.

(music ends)

Jelena: Addiopizzo has evolved into a more ambitious project, so nowadays, they also have a travel agency. Let’s say you want to book a trip to Sicily. You could book it through Addiopizzo, and they would only take you to hotels and restaurants that are part of their network, so you would be sure that no money that you pay goes to mafia. And also, you would be able to go to one of their organised tours.

And this is where Antonio and Edoardo’s path cross. When the Addiopizzo agency was looking for a person that could help them out with the tour of the place where Falcone was killed, Antonio turned out to be their guy. He still lives in Capaci and he still works as a photographer. And today he is sharing his story of that day in 1992 with groups, usually schools and universities

Antonio: Lo facciamo in qualsiasi condizione meteo - con il sole, con la pioggia, con il vento, con il caldo d'agosto….

Jelena: He meets the groups on a hill overlooking the highway, just next to a place where the bomb was detonated from. And today there is a concrete hut painted in white with an inscription in blue: NO MAFIA.

Ben: I wonder if the work Addiopizzo does in Sicily could also be s replicated successfully in places where there hasn’t been such a clear threat as the mafia?

Jelena: So I see Addiopizzo as trust enablers between the system and the citizens. And it is important, because we live in a time when there’s so little trust in the institutions. So it is not about having one specific opponent, it is more about mobilizing the citizens, and reminding them that they have rights and with rights come responsibilities. And this is actually one of the things that I took from the trip, and one of our findings that we had at the end of the conference.

Male voice,Tape from the conference: It is a question for everybody, it not just the question of the shop owner and the mafia, it is also the consumer, so this is culture, so everyone has to feel concern about this topic, and not just the one involving the corruption...

Ben: And so nowadays businesses are doing their business without the mafia involvement? Did they win?

Jelena: I mean...Unfortunately, it is not that simple. But what we can say is that Addiopizzo changed some things and it did help people to gain courage to say no to the mafia extortion. And I think that little by little, it also changes the way the society looks at itself. Raffaella told me this nice story.

Raffaella: Io mi ricordo,bambina, andai un anno in Inghilterra ed ero ospite in una famiglia, andavo a studiare. Avevo nove anni.

Jelena: So when she was a young girl, she went to England to learn the language, and she was hosted there in a family. So one evening they were all sitting in front of the TV, and all of the sudden she saw that something was happening in Italy, in Palermo. You know, her town appeared in the news. And it was related to some mafia murder- again.

Raffaella: E il mio padrone di casa disse: “Ah, tu vieni da Palermo, Palermo- Sicilia, Sicilia - mafia”.

Jelena: So her host turned to her, and said something like “Oh, you come from Palermo, Palermo Sicily, Sicily mafia”. And she felt so ashamed, she wanted to say “Sicily is not just mafia”. She was nine back then, and she tells me that today, at the age of 52 she feels that the things have changed, and she is happy to look back at that time and to tell herself that, yes, she was right and Sicily is not just about the mafia.

Ben: That sounds like a nice story….Although I do not completely understand what she is saying because I have not really spoke Italian since 1990.

Jelena: Well Ben, I guess you’ll have to trust me.

Ben: I do.

Outro.

This has been Episode four of Step One.

Reporting by Jelena Prtoric.

Our editor is Yannic Hannebohn

Our theme music is composed by Niklas Kramer.

A special shout out this time goes to the crew behind the Trust and Transparency project, especially Peppe who knows where to find the best pizza in town.

The teams whose voices you hear in the piece and our team, too, we’re all part of the Bosch Alumni Network.

If you liked this episode, be sure to tell your friends about it. We’ve received a huge amount of positive feedback and we want to thank you for spending your time on this thing. We appreciate it. Also if you want to support us even further, tell one friend about this episode.

Remember the next step is always step one.

This is Benjamin Lorch.

Thanks for listening.

Transcript

Episode 04

"Princess disruption"

© 2018 – Step One Productions

This is STEP ONE

a podcast about people striving to change their world -- our world.

We tell you stories of the Bosch Alumni Network. A network of doers and thinkers connected across the globe working toward positive change.

From Berlin

I am Benjamin Lorch.

And today’s episode: Princess Disruption

But before we dive into our story, we want to introduce you to the community this podcast is part of.

[Jingle]

It’s the Bosch Alumni Network, which consists of people who have been supported, in one way or another, by the Robert Bosch Foundation. The network is coordinated by the International Alumni Center, a think & do tank for alumni communities with social impact. The iac Berlin supports this podcast. If you want to know more about the power of networks, visit iac-berlin.org.

[Jingle]

Ben: So Yannic, you went to New York – and it’s kind of funny that you always keep ending up in a taxi in our podcasts.

Yannic: I was thinking the same thing when I saw what the topic of the workshop. Taxi vs Uber. And to find out more about this controversy, I knew I needed to speak to a Uber driver. So meet Princess.

Princess: The way I go about it is that I get in my car and the first thing that I do is pray. Because you don't want crazy people. Everything you do in life, you gotta have God with you – so first of all I pray and then it's just like, for me, it is just like, I wanna treat people the way... like I wanna be treated as well.

Yannic: So Princess has this new car, very clean. It is like most Ubers, they are pretty clean. But Princess’s car is special. She has a pink leather wheel with fake diamonds on it, and it really suits her overall style. She’s been driving for Uber for about a year now, and she has started working for other driving companies such as Lyft and Juno.

Ben: Well, one thing I liked hearing here is the voice of a woman behind the wheel. I know that the taxi industry was male-dominated for so many years. So this sounds like a change into the right direction and it sounds like Princess has some style.

Yannic: And now let’s switch cars and get in with Eugene, a New York city cab driver.

Eugene: Look what I found in the backseat on the floor. A Cigarette bum. So people still smoke in the vehicle. That is something that almost never happens anymore. That's so rare.

Yannic: So I’m in the car with him and waiting for him to get ready.

Eugene: You are going to see how a taxi driver starts his day...The backpack, I could survive in the wilderness for a week with everything I’ve got in this backpack, food, telephone, band aids, scissors. I once actually a passenger asked me if I had any scissors and I did. (laughing).

Yannic: So we are in his car...You’re feeling it?

Ben: Yeah, I am feeling it.

Yannic: Eugene rides his car, or a car, since 1977. He's this small guy with a slim face. Every day, he drives one hour from his home in New Jersey, to Manhattan, to pick up his cab. And Eugene says he's highly organized and hell, he's right about that. Listen to this.

Eugene: Can't forget my toothpick. You see everything I need is a toothpick. I keep that right there. That'll be needed perhaps later in the day if I eat something. My two tissues, which I have in my front pocket, from home, I keep behind this (haha) on the rubber band. Only on the right side. My music, what should we have today, which probably won't work today in this vehicle, cause it usually does not accept CDs or it'll eat them. Well he we have the Beatles after they broke up some of their best songs except Ringo. cause you know Ringo.

Yannic: Princess and Eugene, they are both drivers in the New York city, little fish in a big sea of drivers. And this sea grew larger and larger from 2011 on, that’s when Uber came and flipped over the taxi system.

(music)

Yannic: Since 2011 till today, the number of Ubers has grown from 0 to 65.000 cars in New York.

Ben: Woow.

Yannic: Yea. And compared to that, there are only about 13.000 yellow cabs. Even when it comes to rides Uber has outgrown taxis by 400.000 to 300.000 daily rides with yellow taxis.

Ben: So is it still possible to earn a living as a cab driver, a traditional cab driver in New York?

Yannic: It’s still possible but it has become less popular.

Ben: Because Uber is such a good employer? That is not exactly what I am hearing.

News collage: For Uber 2017 hast been a year filled with controversies and speed bumps...Uber has fired 20 employees including senior executives. This follows an internal investigation into sexual and other forms of harassment against its employees….Just weeks later a video of Kalanick berating an Uber driver went viral. Kalanick later issued a public apology, saying he’d been seeking help. Uber is also running in local regulatory issues. It’s been sued by disgruntled drivers, criticised for price crouching by customers and faces questions of liability in accidents. Police said it happened Saturday when a driver failed to yield to the Uber vehicle while making a turn, the force of the collision sending the driverless SUV rolling onto its side.

Yannic: So, Uber had its scandals in the last years, and also scandals that lead to the departure of Kalanick, the former CEO of Uber. But still, the drivers that I spoke to were pretty positive about driving for Uber. Not everything about this company is negative.

Ben: No, there has to be something to it.

Yannic: And I want to talk about these positive sides as well, but let’s stick for one moment on the negative sides.

Eugene: I could tell you around the time of 2014, I would say in the spring and early summer of 2014, suddenly you were seeing advertisements for Uber everywhere.

Yannic: In the early days of Uber, drivers could make 5000 dollars per month, before taxes. That was good money.

Eugene: And the advertisement was not particularly aimed for passengers, it was aimed at the drivers.

Yannic: So what did the advertising say?

Eugene: Come drive for Uber. Everywhere you looked, billboards, I mean everybody had an ad for Uber. Talking to the drivers, come ride for us.

Yannic: But as the demand for drivers went down quickly because suddenly they had so many people applying for jobs, the rates for the drivers plummeted.

Princess: Yeah, their cut is way too high, I understand they provide the riders and as well as the drivers, but like we're still doing most the work. If you think about it.

Ben: And how does Uber explain this policy?

Yannic: Well you know, Uber is this company that is just all about technology so of course they would implement a system which is dynamic, based on algorithms. So they would analyse the whole traffic and just adjusts the pricing. So this is why the system is tweaking the numbers all the time. And it is actually not in the driver’s favor. So, to make it more concrete: As an Uber driver your monthly expenses are something about 750 dollars: these go out for insurances, gas, oil and things like clothing and some of the Uber drivers even offer water bottles.

Ben: Wait, so the Uber drivers give out free stuff to their customers?

Yannic: Ahem, yeah, I didn’t get any but yes, they do.

Ben: Why would they do that?

Yannic: Well, probably you didn’t take an Uber or ordered it yourself because otherwise you would know that in the app you can rate the driver from one to five stars. So in this way there’s no need for surveillance of the drivers. This is now done by the users.

Ben: But what happens if a driver doesn’t perform well?

Yannic: They you get deactivated.

Ben: Just like the app?

Yannic: Yeah, exactly.

Ben: What happens in your period of deactivation?

Yannic: So first I wanna ask you, when do you think this happens? At what rating do you get deactivated.

Ben: I don’t know, maybe when they are at an average rating of 3 stars, right at the middle? I mean, average 3 or below, that kind of thing?

Yannic: Ok, it is 4,6.

Ben: Ok, that is the high curve...I don’t know if I am ever going to use Uber, I mean that sounds so Big Brother to me, I don’t like judging other people, I don’t like reading the opinions of others...I mean, it is a mess.

Yannic: Ok, but cheer up, Lorchi. Now we are getting to the good sides of Uber.

Ben: Alright, take me there.

Yannic: Ok, so on a positive note: You have a certain control as a User. Also, as an American, you probably know that yellow cabs had a reputation of being sometimes unfriendly, old and dirty cars, too picky…

Ben: Taxis were notoriously unfair. I guess the Uber app might place a new filter between people and that is probably good. which is both good and bad.

Yannic: And the best argument would be, it is really fun to use, I mean, it really works.

Ben: I am sure. I mean, you can see the system, instead of just an anonymous call, waiting, now you know where the taxi is, and it is literally in your hands.

Ben: So to summarize- the Uber user gains a lot of advantages about transparency, about the estimated waiting, a ride time. Not to mention lower prices at times. But it is clear, it also created some tensions.

Yannic: Yes. And these tensions, I wanted to investigate.

(music)

Yannic: Let’s put all into perspective. Today’s problems of car transportation in New York city are only the newest ones in a long tradition of taxi driving. And for that reason, I went to someone who knows all about it.

Graham: I am Graham Russel Gao Hodges, I am a professor of history at Colgate University and the author of Taxi – a social and cultural history of New York City cab driver.

Yannic: Graham Hodges is what you could call a “taxi historian”. He has been a driver himself for five years in the 70s. And this is what he thinks about Uber:

Graham: Initially there’s a big rush by younger people into doing the service, gradually that expands to a lot of other people, older people who need rides to places where’s difficult to get a cab, African Americans find it often attractive because yellow cab has a really bad reputation for not picking up people of color, and the Uber was at least nominally doing that.

Princess: I would hail a taxi over a black car but the taxi drivers are really bad. A lot of them stink, like really bad, a lot of them are racist. You would hail a cab, let’s say me and a guy, specifically a black guy, he would hail a cab, and the driver would have no one but he would not stop. He would just keep going. Or he would stop and ask where we are going which, by the law, you are not supposed to. But he will ask where you are going and you’d say I am going to Brooklyn coming from Manhattan and he will say I am not going there. And drive off..

Graham: Taxi companies have been notoriously greedy, and cab driving has gone through major transformation in staffing over the last 40 years. Particularly in the use of lease-hire contracts.

Ben: Lease hire contracts? Like when you you lease a car from the company and drive for just for a week or so?

Yannic: By using that model you will have to first earn what you advanced for being able to ride in the first place. So, let’s say, in a normal week, you would have these expenses and you are covering up for them by Monday, by Tuesday, and only by Wednesday maybe you start earning money. And with that other model, like with Uber, you get money from your first ride on basically. Because you don’t have the advances.

Ben: Right, so it makes sense why so many drivers would switch to Uber.

Yannic: Yeah, if they don’t own a license themselves.

Ben: Right, the medallion system.

Yannic: Can you try to explain that to the listeners?

Ben: Sure. The yellow cab drivers would buy a medallion from the city which was the license for operating a cab in New York. And these licenses were limited in number and therefore extremely valuable. Before Uber entered the market these medallions could fetch up to one million dollars when bought and sold on the open market. They were considered a “ticket to the middle class.” And then the prices dropped. Dramatically.

(music)

Eugene: He are first leasing the medallion. And then you’re thinking, I want to own one, instead of paying somebody else’s medallion, or paying off somebody else’s medallion. I am going to pay for my own medallion. And here is what you need to do to buy a medallion worth a million dollars. That is selling for million dollars. You would have to come up with 70, 80, 90 000 as a down payment. If you are a taxi driver that means that you are probably going to work like a slave for six, seven years, something like that.

So 2014 was arrived and all these guys who had worked like that to save money for the down payment suddenly had nothing. Look what he looks like in the eyes of his wife, in the eyes of his children, in the eyes of all the people he knows in his life. Because this guy was trying to achieve a big step up from the poverty. And now they're wiped out. And for some people that's enough to commit suicide.

Yannic: This is the reason I was asking Hodges, the taxi historian why the city would allow Uber to the market in the first place. I get why the users and the drivers would accept the new technology, I accept it myself. But technically this practice was still illegal. I mean at least in Europe this wasn’t possible. The European court ruled that Uber should be regulated like a traditional taxi company.

Graham: I understand that as a German you are confused by that because Germans in general obey laws. Uber in general likes to describe itself as a disruptor. And they have done this in a number of cities, they did it in New York. They simply say “we are here and we are established and sue us if you want to stop us”. And so once they get into that kind of political and legal battle, they operate and increase their numbers because Uber is extremely well funded. There is a lot of speculative money going into Uber which helps them establish a presence even though it is not legal. And you know, police department in NYC has a lot more important things to do than regulate taxi cabs.

Yannic: And that’s the moment when it sank with me. That in the US, it is okay to trust the market and what they call “disruptors” to come up with an idea to innovate a system.

Ben: But I mean, Uber still needs to be regulated, I think.

Yannic: Yeah, I think so too. So I went to this workshop organized by the Bosch Alumni Network and the Global Diplomacy Lab. We were in Brooklyn, in this nice loft. A lot of participants were there and I was eager to see what they would come up with.

Ben: And who were the participants?

Yannic: They came from the public sector, from NGOs or foundations, and they were all people interested or involved in one way or another in policy making. It was kind of an interesting combination of people. The method of the workshop was design thinking.

Ben: Alight tell me, what is Design Thinking?

Yannic: To begin with, it’s about breaking your constraints. This means that within the process you first have to write down everything you think you know about the topic. That means prejudices. False assumptions. So let’s say you had to interview an Uber driver,which is basically what they did at the conference.

Ben: Were they interviewing anyone else.

Yannic: Yeah, taxi drivers, experts...transportation policy makers, so the idea was to get all the opinions on board. So while the groups were working, the journalist I am, I interviewed some of the experts myself. Because I too, had questions that I wanted to have them answered. So I went to this one expert, Paul Lipson, he is a consultant working in clean transportation and the renewables and I asked him how he sees the shift of power in this sector, and what the future holds for the industry.

Yannic: The moment you outsource the public transportation to a company you lose independence, because at some point Uber will become….critical…

Paul: Indispensable part of the transportation system….

Yannic: So how would you, how should New York deal with that?

Paul: It will be another disruption. Let’s remember, yellow cabs were a critical part of the transportation system, they no longer are. They were disrupted. Uber is gonna be disrupted by autonomous driving, Uber is going to be disrupted by any number of things, especially I think congestion pricing, that will tend to mitigate the impacts and limit the benefits to the company for being in New York City.

Yannic: So you are just waiting for the next wave to come….?

Paul: If I was a policy maker; I would be accelerating that wave, I would be building into the congestion pricing bill, that discourages use of single occupancy vehicles for livery, for taxi fares and that encourage ride sharing, clean transportation, encourage bicycling. All the things that will make New York city cleaner, and more livable, and ultimately more equitable too.

Ben: Isn’t design thinking also a way of totally disrupting ecosystems that have formerly existed?

Yannic: Yes and no. Innovation is a double edged-sword it can harm, it can do good. I asked the design thinking coaches from the workshop. They are called Ektaa Aggarwal and Alessandra Lariu, I asked them about this dilemma. And they told me-it is a tool. It’s up to you what you make out of it.

Coaches: Every time we create something new using this method...it is not necessarily that you can predict how it is going to go when it’s out in the world; doing its thing. I think an analogy to use is – imagine a baby is born, like you used design thinking and now you have a baby. Now if there’s now parental guidance, you can’t blame the baby for being a crazy kid. You have to parent the baby in the way you want the baby to be raised, with a decent knowing of right wrong and morals and civic code of society, and so you can’t blame the baby that had no supervision for how it’s turning out, it’s you job as a parent to... Once innovation is born into this world, through the process of design thinking and creativity, there are other systems that need to come into action and place...

(music)

Ben: So how did the groups in the workshop perform? Did the create any new stuff? Did they innovate, ideate - that’s the design thinking term, right? Any sorts of solutions, any step ones?

Yannic: One group who thought of refinancing the driver’s lost medallion money by creating this billboard, advertisements for the yellow taxi. There was also the “Beehive group”, that came up with the idea of a common space for Uber and taxi drivers in the city, where they could rest, have access to toilets. And then there was this group called Driving change. They focused on the high competition among the drivers and also on the animosity between the drivers and the clients.

Tape from the conference:

So should we just sit down and do it…

How much time do we have?

I have no idea…

Probably not enough…

That should not go out...

Yannic: During their pitch you will hear them play different roles basically, using quotes from the interviews they conducted.

Ben: Ah, they are users themselves.

Yannic: Yes.

Driving change group pitch:

- It’s the best of times, it’s the worst of times. It’s very sad, I like the technology. But I don’t want technology to kill jobs.

- Hi, I’m VJ, I’m from Pakistan I live here in New York for the last 5 years. I was a taxi driver before but then I moved to Uber because I found it very interesting. But to be honest, I’m a bit anxious - I keep hearing about a lot of things, that cars are not going to have drivers, anymore in the future, or that the market is very competitive right now.

–My name is Ann Davies, I’m 67 years old. I enjoyed my retirement, since three years. My husband passed away 2 years back, so sometimes I feel lonely.

Yannic: Their proposal was to implement a new rating system that would match drivers and clients on a personal level based on similarities and then to create a more natural experience, during that intimate moment that is a ride basically. Because in a few years, there might be no more need for Eugene and not for Princess anymore. I mean, no need for any drivers at all.

Driving change group pitch: We’re gonna transition into an industry, these jobs may disappear in the future. So we have to be prepared for it. And how we’re gonna create empathy towards people who are going to lose their jobs. Everyone here took an Uber, and how many times did you talk to the Uber driver? If a machine would substitute the Uber driver, would that change the experience? Probably not nowadays. So the idea would be to bring back this personal aspect to it and make people have empathy.

Princess: I personally like that. I like he aspect of getting to know people. Even though I am never gonna know you again, at least I met this person. And it is just for maybe five minutes, maybe ten minutes...I get customers that sometimes they actually need to talk because they have so much on them. You know, I feel like now we have the phones and the apps, like you said and all these other stuff, especially in New York, we don’t really pay attention to other people, we don't really try to get to know other people. But when a person gets in my car, we're gonna have this quick conversation and hopefully both of us leave this car with something new. With something that made us happy. And I think that's my passion. Like, I love to see and make people smile. So, I like it, I love it. It's great for me.

Yannic: Thank you, Princess.

Princess: No problem....

Yannic: On Saturday evening, at the end of the workshop, the design thinking jury announced the winner of the competition.

Conference tape: And the winner is …. Driving change (applause and laughs)

Outro.

This has been Episode four of Step One.

Reporting by Yannic Hannebohn

Our editor is Jelena Prtoric.

Our theme music is composed by Niklas Kramer.

A special shout out this time goes to all the lovely people who came to our recent launch party in Berlin to discuss this episode with us, support us and celebrate with us. Lots of love!

The teams whose voices you hear in the piece, presenting their innovations during the workshop, and our team, too, we’re all part of the Bosch Alumni Network.

If you liked this episode, be sure to tell your friends about it. We’ve received a huge amount of positive feedback and we want to thank you for spending your time on this thing. We appreciate it. Also if you want to support us even further, tell one friend about this episode.

Remember the next step is always step one.

This is Benjamin Lorch.

Thanks for listening.

Transcript

Episode 03

"Taxi to Sarajevo"

© 2018 – Step One Productions

This is STEP ONE

a podcast about people striving to change their world -- our world.

We tell you stories of the Bosch Alumni Network. A network of doers and thinkers connected across the globe working toward positive change.

From Berlin

I am Benjamin Lorch.

And in this episode we take a taxi to Sarajevo

But before we dive into our story, we want to introduce you to the community this podcast is part of.

[Jingle]

It’s the Bosch Alumni Network, which consists of people who have been supported, in one way or another, by the Robert Bosch Foundation. The network is coordinated by the International Alumni Center, a think & do tank for alumni communities with social impact. The iac Berlin supports this podcast. If you want to know more about the power of networks, visit iac-berlin.org.

[Jingle]

[sounds of inside a car]

Yannic: It’s a Monday morning in early September and I am in a cab from Sarajevo airport to the city center.

Driver: You come from?

Yannic: I am from Germany.

Driver: Dann reden wir lieber Deutsch.

Yannic: Du sprichst Deutsch?

Driver: Besser als Englisch

(laughs)

Yannic: Emily, an American reporter you might have caught laughing in the backseat, and I – we are here to report on the elections in Bosnia on October 7th. Sarajevo. I’m new to this city, and I am also new to reporting from the Balkans.

So, what’s up with the elections?, I ask my driver casually. He laughs. We’re full of it, he says. Nothing new happens. They promise you everything and then – nothing changes.

Driver (in German): Es passiert nicht neues. Die versprechen viel vor den Wahlen, nach den Wahlen passiert nichts.

Yannic: What I know about Bosnia is based on a prep talk I had with Jelena, our editor, – and the BBC documentary series, “The death of Yugoslavia”. It’s basically a crash course for foreign reporters. A short history of what happened in the Balkans and in the Bosnian war between 1992 and 1996. The documentary shows how nationalist Serb forces besieged Sarajevo for almost four long years. Almost 14.000 people died during the siege and more than half of them were civilians.

The driver tells me he fled to Hamburg during the war. He was always working, even there, he points out. No social assistance. He headed back home, as soon as the war was over.

If he had the power in this country, he would get rid of all the old politicians, he says. Let the younger people lead the country. Old politicians brought us nothing, 25 years after the war and where are we now?

Driver (in German): Wenn ich Macht hätte würde ich alte Politiker entfernen. Lasst neue intelligente Leute das Land zu führen. Die alten Politiker haben uns nichts gebracht, 25 Jahre nach dem Krieg. Und wo stehen wir?

Yannic: We drive by a campaign billboard, I see an almost bald man, grinning.

Jelena, she explained me parts of the political system in Bosnia. It’s very confusing, tangled, she says, to a point where I’m wondering if the elections can have any impact on the country, really.

We drive on a highway, Sarajevo is to our left. I lean forward and I peak through the window, the bright sun illuminates the houses and few skyscrapers patched together like a puzzle.

20 minutes in, the driver pulls over. I ask for his name.

Driver: Essad

Yannic: I’m Yannic, I say.

Perfect.

(music)

Yannic: So my trip has begun and I am only scratching the surface of something that is to me unknown, Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Ben: What were your thoughts after this first encounter?

Yannic: I saw some patterns, such as “My vote won’t change anything”. Also, there is this other pattern that people are leaving the country to find something else. I also felt that Bosnia is complicated. Because of Bosnia’s past, the war and the ethnic divisions. To be honest, I even had more questions.

Ben: Like what? What else was on your mind?

Yannic: Like, the feeling that I had when I was talking to the driver, I felt really that he was indifferent about the elections?

And, what are people of my generation thinking?

Ben: And you were there for a study tour on the Bosnian elections organized within the Bosch Alumni Network? Is that right?

Yannic: Right. We were twelve, and we were journalists from all over the world basically. And we were there because four of them, and that is Emily, the woman that was in the cab with me; and Jelena, they organised the trip, together with Almir. He is Bosnian, and he secured us access to all these great sources during the week. We were with the prime minister for example..

Ben: Wow, all right.

Yannic: Yeah. And political analysts, younger journalists…

Ben: Nice, sounds like your access was quite good.

Yannic: It was. And Sarajevo is just completely beautiful. Before it became part of the socialist Yugoslavia, Sarajevo was conquered by the Ottomans by the Austrians. And you don’t really have to be a culture nerd to see this. When you walk around the city center, you stumble across a Cathedral, a mosque, a synagogue and an Orthodox Church within a radius of 500 meters. The market stands are also pretty exciting. They display stuff like Bosnian coffee pots – they look like small kettles, but they have this straight handle. Also you would find oriental carpets and jewellery...And then there’s Kafana.

(fade into kafana music playing)

Ben: What is kafana?