Yannic goes to Sarajevo to try to understand the complicated world of Bosnian politics ahead of the general elections. There he discovers kafanas.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is often considered home to one of the most complicated political systems in the world. In early-October, citizens will vote for the country's three presidents and MPs in multiple national assemblies. As a young state, this is only Bosnia and Herzegovina 8th general election but many citizens seem to be disillusioned by the politics and feel that their vote cannot and will not change anything. Yannic navigates the complicated world of Bosnian politics to look for where a new change might come from.

Bosch Alumni Network Event:

Bosnian Election Study Tour

Sarajevo

September 2018

Music in this episode:

Arrows of the Sun by N. Kramer

Polygons by Paternoster Poetry

Puzzle Pieces by Lee Rosevere

Get ready by Komiku

One cool Minute by Loyalty Freak Music

I came back downstairs and you were gone by Paternoster Poetry

Additional Information & Resources

Video:

"The Death of Yugoslavia"

BBC Documentary, Part One

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vDADy9b2IBM

Yannic's Interview with Edin Kukavica

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xAk7_r2KXlc

PHOTOS:

Bosnian election study tour group in front of the Eternal flame memorial in Sarajevo. Credit: Kemal Softić/iac Berlin

Sarajevo by night. Credit: Kemal Softić/iac Berlin

Bosnians are very, very proud of their coffee. Here, in front, some Bosnian coffee pots (džezva) and cups at the central market of Sarajevo. Credit: Kemal Softić/iac Berlin

Our reporter, Yannic, recording a guided visit of the central Sarajevo. Credit: Kemal Softić/iac Berlin

The group in Sarajevo Town Hall. Credit: Kemal Softić/iac Berlin

EPISODE 03 - Taxi to Sarajevo – Transcript

Transcript

Episode 03

"Taxi to Sarajevo"

© 2018 – Step One Productions

This is STEP ONE

a podcast about people striving to change their world -- our world.

We tell you stories of the Bosch Alumni Network. A network of doers and thinkers connected across the globe working toward positive change.

From Berlin

I am Benjamin Lorch.

And in this episode we take a taxi to Sarajevo

But before we dive into our story, we want to introduce you to the community this podcast is part of.

[Jingle]

It’s the Bosch Alumni Network, which consists of people who have been supported, in one way or another, by the Robert Bosch Foundation. The network is coordinated by the International Alumni Center, a think & do tank for alumni communities with social impact. The iac Berlin supports this podcast. If you want to know more about the power of networks, visit iac-berlin.org.

[Jingle]

[sounds of inside a car]

Yannic: It’s a Monday morning in early September and I am in a cab from Sarajevo airport to the city center.

Driver: You come from?

Yannic: I am from Germany.

Driver: Dann reden wir lieber Deutsch.

Yannic: Du sprichst Deutsch?

Driver: Besser als Englisch

(laughs)

Yannic: Emily, an American reporter you might have caught laughing in the backseat, and I – we are here to report on the elections in Bosnia on October 7th. Sarajevo. I’m new to this city, and I am also new to reporting from the Balkans.

So, what’s up with the elections?, I ask my driver casually. He laughs. We’re full of it, he says. Nothing new happens. They promise you everything and then – nothing changes.

Driver (in German): Es passiert nicht neues. Die versprechen viel vor den Wahlen, nach den Wahlen passiert nichts.

Yannic: What I know about Bosnia is based on a prep talk I had with Jelena, our editor, – and the BBC documentary series, “The death of Yugoslavia”. It’s basically a crash course for foreign reporters. A short history of what happened in the Balkans and in the Bosnian war between 1992 and 1996. The documentary shows how nationalist Serb forces besieged Sarajevo for almost four long years. Almost 14.000 people died during the siege and more than half of them were civilians.

The driver tells me he fled to Hamburg during the war. He was always working, even there, he points out. No social assistance. He headed back home, as soon as the war was over.

If he had the power in this country, he would get rid of all the old politicians, he says. Let the younger people lead the country. Old politicians brought us nothing, 25 years after the war and where are we now?

Driver (in German): Wenn ich Macht hätte würde ich alte Politiker entfernen. Lasst neue intelligente Leute das Land zu führen. Die alten Politiker haben uns nichts gebracht, 25 Jahre nach dem Krieg. Und wo stehen wir?

Yannic: We drive by a campaign billboard, I see an almost bald man, grinning.

Jelena, she explained me parts of the political system in Bosnia. It’s very confusing, tangled, she says, to a point where I’m wondering if the elections can have any impact on the country, really.

We drive on a highway, Sarajevo is to our left. I lean forward and I peak through the window, the bright sun illuminates the houses and few skyscrapers patched together like a puzzle.

20 minutes in, the driver pulls over. I ask for his name.

Driver: Essad

Yannic: I’m Yannic, I say.

Perfect.

(music)

Yannic: So my trip has begun and I am only scratching the surface of something that is to me unknown, Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Ben: What were your thoughts after this first encounter?

Yannic: I saw some patterns, such as “My vote won’t change anything”. Also, there is this other pattern that people are leaving the country to find something else. I also felt that Bosnia is complicated. Because of Bosnia’s past, the war and the ethnic divisions. To be honest, I even had more questions.

Ben: Like what? What else was on your mind?

Yannic: Like, the feeling that I had when I was talking to the driver, I felt really that he was indifferent about the elections?

And, what are people of my generation thinking?

Ben: And you were there for a study tour on the Bosnian elections organized within the Bosch Alumni Network? Is that right?

Yannic: Right. We were twelve, and we were journalists from all over the world basically. And we were there because four of them, and that is Emily, the woman that was in the cab with me; and Jelena, they organised the trip, together with Almir. He is Bosnian, and he secured us access to all these great sources during the week. We were with the prime minister for example..

Ben: Wow, all right.

Yannic: Yeah. And political analysts, younger journalists…

Ben: Nice, sounds like your access was quite good.

Yannic: It was. And Sarajevo is just completely beautiful. Before it became part of the socialist Yugoslavia, Sarajevo was conquered by the Ottomans by the Austrians. And you don’t really have to be a culture nerd to see this. When you walk around the city center, you stumble across a Cathedral, a mosque, a synagogue and an Orthodox Church within a radius of 500 meters. The market stands are also pretty exciting. They display stuff like Bosnian coffee pots – they look like small kettles, but they have this straight handle. Also you would find oriental carpets and jewellery...And then there’s Kafana.

(fade into kafana music playing)

Ben: What is kafana?

Yannic: I don’t speak Bosnian but for me kafana means “having a good time despite all of your worries”. You go into these bars and there’s a band playing. They go from table to table basically and play you some songs. And people start getting up, they react to music, they get up and dance, and this happens almost immediately.

Ben: Alright, it sounds like Kafana could be a good place to start exploring the social dynamics.

Yannic: Well, at first, first night, I was more than sceptical. But on the second night already, in the second kafana, there was no way escaping it. People were grabbing me, they were like, ‘Yannic, are you gonna come?’, they were basically inviting me to dance, to sing along even. I didn’t know the lyrics, because I don’t know Bosnian…

Ben: Okay, but there seems to be a contradiction between this joy of Kafana and the current political frustration.

Yannic: Yeah, at first, it seemed strange to me, too.

(music fading)

Yannic: On my only free day, I set out to explore. I decided to spent some time with a young woman we met during the conference. Her name is Naida. She’s 22, she’s pretty tall, one meter eighty or so, she’s got light brown hair, and she looks very athletic.

Naida: Nice to meet you..we were together after we finished

Yannic: You were in the car...

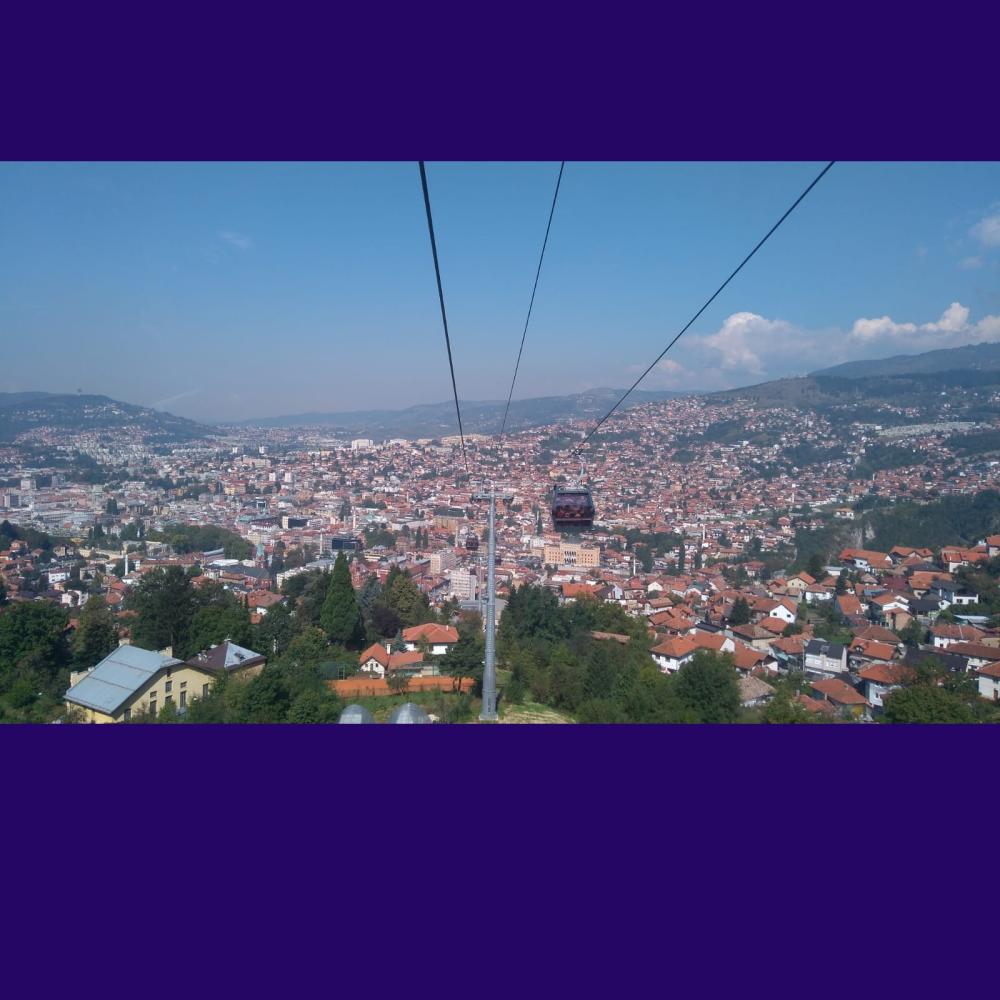

Yannic: We head to the cable car of Sarajevo - it’s one of Naida's favorite places in the city.

(music)

Yannic: Uphill we walk around and enjoy the view over Sarajevo. We chit-chat for a little bit. We walk around with no real destination …. and then maybe thirty minutes into our conversation – we find a connection. Naida tells me about a terrible accident she had only five months ago.

It was during a volleyball match.

Naida: It was in the third set, practically at the end of the game. I played the first two sets and the trainer than said Naida you should stay out, we can do that without you. And then when the result in third set was 20:20 he called me to come in, and he tell me... he….hug...He hugged me and said, you should make a score...you can make a score, we need you now. And I make two scores and after that…

Yannic: Her ankle twisted so bad, that she had to go to the hospital.

Naida loved volleyball, she played since she was 9 years old. For her it was more than about exercise or success. It was the sense of sisterhood, belonging to a group, having the same goal and working hard for it.

Naida (in Bosnian): And there was the fact that the girls also believed in me. When there was a difficult situation, they would say ‘Naida will do it’. This is what was giving me strength.

(in English) Sorry, I am a little bit sensitive.

Yannic: Ok, sorry, I didn’t want to evoke these feelings.

Yannic: It’s heartbreaking even if I don’t understand all the details. Searching for something to say, I ask her: Isn’t there a goal that Bosnia can pursue as a team?

Naida: The best goal for the country should be that nobody should be separated in three different groups of people. We have here three ethnicities, Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats and in my opinion we should all be Bosnians.

Ben: Is there a party that corresponds to this idea of unity Naida has? Who is she voting for?

Yannic: Well, she is not voting actually. She told me that on the election day, she would take her ballot paper, she would take a pen, and just cross it over.

Ben: She’s going to spoil her vote?

Yannic: Yeah.

Ben: Why would she do that?

Yannic: Exactly. That’s what I asked her.

Yannic: But why? Is there not one candidate that speaks for you?

Naida: I don’t think that anyone of them can make something better. They all say always the same sentences. I will do that I will do that, I am better than him.They only talk. And don’t do anything.

(music)

Ben: Yannic, now tell me. I got to step back. I know this is the general election but how exactly does the electoral system work in Bosnia? How does the voting system work?

Yannic: It dates back to the Dayton peace agreement. December 14th, 1995. It was signed in Paris by the representatives of the international community and by the leaders of the former Yugoslav states in conflict.: Bosnia, Serbia, Croatia. The Dayton agreement put an end to the war in Bosnia that pitted three different ethnicities against each other. It brought peace to the country – but it also changed the Bosnian constitution significantly. Ever since, Bosnia is divided into two parts: the Republika Srpska, and the Federation, which are mostly Bosniaks and Croats.

Ben: And what are the differences between these ethnicities?

Yannic: Well, there are mostly religious differences. So the Serbs are Orthodox, Bosniaks are mostly Muslim and Croats are Catholic.

Ben: Okay. And at this point how independent are these two parts?

Yannic: Both entities, both parts of Bosnia, the Serb and the Federation, hold individual parliaments, bureaucracies and individual courts, which makes the Bosnian administration huge – for a country of 3 and a half million inhabitants. On the highest, on the state level, there’s another Parliament and representatives from the two entities, plus the presidency which is chaired by three presidents, one of each ethnicity: There’s a Bosniak president, a Croat president and a Serb president, with each ethnicity voting for its own president. Did you understand that?

Ben: Yes, I did understand it, but now I have forgotten it.

Yannic (laughs): Can you explain it back to me?

Ben: No!

Yannic: So if you didn’t understand all of it now, let me play you some tape of how I struggled during the week.

Ben: Okay.

Yannic: This is us, Aleksandar, a Macedonian journalist, Kemal, the photographer that escorted us during the week and me. We are passing by a big banner of the SDP party, the social-democrats in Bosnia, and I spot something unusual about it.

Yannic: The spd is the only party with 4 candidates.

Aleksandar: So they have a candidate. Denis Becirovic and he’s Bosniak.

Yannic: Aha, ok.

Aleksandar: So you can not vote for a Serbian candidate here.

Yannic: But they have different candidates in the Serbian part, in the Republika Srpska.

Aleksandar: I guess.

Yannic: Okay. But Magazinovic does not run, because he’s not Bosniak...He is a Serb.

Aleksandar: Only for the Parliament.

Yannic: Yea. He’ll run for Parlament

Aleksandar: He’ll run for Parlament

Yannic: As a Serb in Bosnian territory, in Sarajevo.

Aleksandar: Yeah.

Yannic: That’s so complicated. Especially for my German brain (laughs)

Driver: Hat-Tschi. (sneezing)

Yannic: Gesundheit.

(mumble)

Ben: Indeed it seems that you were pretty confused.

Yannic: By now, I understood most of it. But there’s still so many details that I didn’t get, I fear.

Ben: Is this why people are disillusioned by the political system?

Yannic: It must be one of them. But honestly I also feel that it has a lot to do with how the politicians are speaking and what they are saying.

[Tape of Bosnian politicians - Saša Magazinović, Šefik Džaferović and Fahrudin Radončić - speaking]

Yannic: For me they sounded almost too similar. Like, I couldn’t really tell the difference. And also their salaries are around six times higher than the average Bosnian wage, which is just over 400 euros net. This makes the Bosnian members of parliament the best paid MPs in Europe, if you compare them to average wages in their respective countries. And because of that, many feel that one goes into politics – only – to get rich.

Driver Essad (in German, in the background): Es gibt viele junge Leute die haben Schule fertig, die haben Uni fertig und die haben kein Job. als einziges ausweg die Denken: Ok, dann geh ich in irgendeine Partei, damit sie dann da einen Job finden. Ich brauch das nicht. Man kann aber nichts dagegen sagen, die Leute haben (sic). 12, 13 jahre in die Schule gegangen, studiert. Ohne Job. Man kann da nichts sagen.

Yannic: This is also what Essad - you remember the driver, that brought me to Sarajevo? - told me: young people either go into politics, to earn what they can earn, or leave to the West, the EU mostly.

He also says that with the lack of real options in this country – you can’t even blame them.

(music)

Yannic: It is the last day of our study trip, and we’re meeting this political analyst, Ivana Maric, in a café in downtown Sarajevo. I ask her about it, about the youth of Bosnia.

(music)

Yannic: I would like to ask you a question about the younger generation, because they told me, they are leaving the country, they want to go West, because they want to invest in their future, because apparently being a hairdresser in Western Europe is still better than being nothing here. How do you explain that?

Ivana Maric: I don’t think that you can live better as a hairdresser somewhere else than here. You can live really nice here, if you like that. People think ….they don’t even try here. Especially people with an university degree. They say, I am going to live abroad in Germany, but you have to work hard there to succeed and they did not even try, we have…

Yannic: And then… one journalist of our group, Aleksandar, he is an investigative reporter from Serbia, bursts out. He’s sitting in the back so it’s hard to understand him but he’s angry about Maric’s view on the mentality of the people.

Aleksandar: I have a problem, many people from this region, especially in Serbia, I hear it very often. After thirty years of ruining this countries in this area, we are putting the blame at the common people. That really bothers me because that same people were very good from 1945 to 1990, the same people were building, our grandfathers and our parents were building this country, they were very hard workers, very good scientists, it was a good life. And after thirty years of wars, sanctions, killing each other and ruining the system and corruption, in the end, all we need is to blame the people.

Ivana Maric:I understand what you said but i don’t like to be...victim, we are not victims, actually. If you vote for somebody for twenty years than you are not a victim. We all have this mentality…

Aleksandar (in the back): The option to go abroad?

Ivana Maric: No, the option to fight here…

Yannic: This goes back and forth for five minutes or so.

Aleksandar: I really disagree. People are really aware that they live in a corrupted system. And they don’t have any hope because the professors from the university are corrupted, judges are corrupt, policemen are corrupt ...politicians are on the top of this pyramid, and we expect from the common people to do what?

Ivana Maric: Actually I was never a victim and I don’t want to play victim, I can change something….

Yannic: Until it ends.

(music)

Yannic: As we walk out of the café, I have the chance for a quick chat with Aleksandar, who still seems to be agitated by the discussion.

Yannic: You didn’t like her?

Aleksandar: No, I am almost becoming mad when I hear this opinion. All we need is to put the blame on the common people. You are not good enough, you don’t work enough..pure neoliberal thoughts, you know. Like treating people like slaves, they don’t have any right, every institution in this country is ruined and corrupted and what do you need? Work harder? What does it mean, work harder?

(music)

Almir: It’s not normal that young people from Bosnia go to Germany and become good workers. And that the same young people in Bosnia are not good workers.

Yannic: In the evening, on that same day. I meet up with Almir, who lives and works in Sarajevo. He’s one of the organizers of the study tour. And in the car we start discussing the argument that Ivana Maric and Aleksandar were having earlier.

Almir: It’s not normal because it’s the same person in Germany and in Sarajevo. It is the same mentality. But when someone goes to Germany and becomes a worker in some factory, he has some kind of system. The main thing is perspective. Why perspective? The young people in Germany and in Bosnia are the same young people. But the only difference in Germany is that they can see and predict and make plans for the next ten years.In Bosnia the people are living day for day.

Yannic: He blames the generation of his fathers and grandfathers for the current situation in the country.

Almir: They destroyed the country in privatisation in stealing from the tenders and so on. My generation is still coming. I believe that that generation will love the country more than a few generations earlier.

Almir: I have to find a parking place. You can tape that.

But I have to leave this to my friend who is working on parking. He is a night shift. He’s probably works for 150 euros per month.

Yannic: Does that sadden you?

Almir: Yeah, but it’s a problem because we’re something like an unhappy society with a great potential. We’re hedonist. We like to be hedonist. We like to drink coffee, look on the city, on the viewpoints and enjoy it but believe me, sometimes we have to be fighters…. Come on.

(door slams)

(music)

Yannic: We walk through the center of Sarajevo. The sun has set, and the streets fill up with people. It’s a Thursday night. Almir leads us to a shisha place with lots of wooden benches outside. There’s pop music playing in the background, the air is filled with the sweet flavour of mint Shisha. And he orders us a pipe. For the first time during that week, I’m relaxing.

Yannic: In the car we were talking about fighting the fight, you were saying basically that Bosnian should keep fighting the fight. What is your personal fight?

Almir: Huh. I don’t know. right now i don’t know. Why? Because it is a very tough question for young generation in Bosnia. Why? We are not so stupid. We know what’s happening in the world, we know new techniques, we have some jobs, someone have good jobs, like me, we have friends in all parts of the world. We understand differences in East and West, we understand what Russia wants here, we understand that the US is powerful, we understand that we want to the EU. Not because we are in love with the EU, no because, we are Europeans.

Ben: Right, potential EU membership. A whole other layer...

Yannic: That’s the topic that has been whizzing around every conversation in that week. Europe, the EU. Bosnia is waiting for its candidacy status for quite some time now. It’s the one thing that nearly everyone in this country can agree.

Ben: Could they join the EU anytime soon?

Yannic: Not really. The Eu says that Bosnia has a lot of “homework” to do. This is mainly fighting against the corruption and organised crime. It’s the reform of the judiciary system and the public administration.

Edin Kukavica: Joining the EU and NATO is the only solution for Bosnia and Herzegovina in this moment and for all our future.

Yannic: Edin Kukavica is a publicist and the director of a cultural center in Sarajevo.

Edin Kukavica: Unfortunately it will take more time than we like to talk about.

Yannic: In his books Kukavica describes a revolution within the people, that for him is a first step towards a prosperous Bosnia. I got the chance to interview him after a group meeting.

Edin Kukavica: That revolution that I’m writing about, is first of all a revolution inside of every single person in this country and in every national course, a revolution among the Bosniaks, revolution among the Serbs, among the Croats and whoever else exists here. Just to think about Bosnia as our home country, as our home in the full meaning of that word. Not to think about the different entities. We need that revolution on that level of consciousness and awareness of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This is the first revolution, private, intimate, inside revolution.

(music)

Ben: Is this their step one? A revolution within themselves?

Yannic: What I saw is that the young generation is already taking their first step. They’ve proven to be hard workers and are pushing the system to its limits. While speaking to Almir, Naida and all the others, I saw a lot of determination. A determination to go forward.

And I saw a lot of kafana.

Ben: I’m pretty sure we’ll have to check with Jelena on the real concept of kafana. But I really am starting to get it.

Yannic: Go check, go check. But until you do that, should I play some more music?

Ben: Sure. Do you wanna dance?

Yannic: Sure.

Ben: Can I buy you a drink?

Yannic: (laughs)

(music up and fade)

Almir: I believe these people need something like celebrations. For 20 years we didn’t have any celebrations, any sports success that we can celebrate, any cultural thing we could celebrate. We didn’t have any Nobel prize winner in the last 3 decades, before we had them from literature to chemistry. AndI think the political elites if they understand this country, they should invest and improve some part of the society, like sports. We need something to bring back the smile on the faces of ordinary people. That’s something that we need.

(Music fade)

(Outro)

Ben: This has been Episode three of Step One.

Reporting by Yannic Hannebohn.

Our editor is Jelena Prtorić.

Our theme music is composed by Niklas Kramer.

We have a special shoutout to Almir. Why? Because of his catch phrase “We can arrange this.”

Almir Šećkanović, Emily Schultheiss, Aleksandar Đorđević, Aleksandar Janev and our team, we’re all part of the Bosch Alumni Network.

If you liked this episode, be sure to tell your friends about it. We’ve received a huge amount of positive feedback and we want to thank you for spending your time on this. We appreciate it.

If you want to see pictures of Sarajevo by the official photographer of our study trip, Kemal Softić and an uncut video interview of Yannic with Edin Kukavica on the political forces in Bosnian politics, visit our website at www.stepone.berlin.

Also if you want to help us, you can rate Step One on Apple Podcasts and and click on your computer and have fun.

Remember the next step is always step one.

This is Benjamin Lorch.

Thanks for listening.